If you were to take a minute to research the current medical heroes in our society, I’m sure you would be overwhelmed with hundreds of names. However, in Ancient Rome and Ancient Greek societies, there are only so few of them. The reason for this includes the fact that an education in the field of medicine did not exist in Rome until the 2nd century C.E., so anyone could classify themselves as a doctor without having any theoretical knowledge and previous experience.

Hippocrates of Ancient Greece:

aka “father of medicine”

Hippocrates was born in 460 BCE, and lived during the Greek Classical Period. To have the lineage of knowledge from such a long time ago, there are around 60 medical writings that have survived about him, most written by others and not Hippocrates himself. He took on the main role as a physician and teacher.

To understand the great influence Hippocrates had, the Greek physician Soranus wrote about the entire life of Hippocrates five hundred years later. He traveled around Greece and around Anatolia to practice his art and teach others at medical schools. Unlike many other physicians, Hippocrates rejected superstitious beliefs that supernatural forces were acting upon diseases. He distinguished medicine and religion as two distinct disciplines, arguing that disease was not a punishment from god but rather the effect of environmental factors, including diet and everyday habits. Unlike modern medicine, the Hippocratic school focused on patient care and prognosis, rather than diagnosis, allowing for a great improvement in clinical practices. The more holistic approve, deviates from modern focuses on specific diagnosis and individualized treatment.

Two important pillars of the Hippocrates school

[greek] Dyscrasia- dus (bad) + krasis (mixture)

- When the four humors (blood, black bile, yellow bile, and mucus) were imbalanced, one would become sick until the balance was restored.

[greek] Crisis – krinein- decide

- A point in the progression of disease, when the illness began to overtake the body and the patient would submit to death, or on a positive note, natural processes would allow the patient to recover. Due to relapse, the crisis usually had a domino effect. Galen (Roman Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher) connected this belief back to Hippocrates.

Galen of Ancient Rome

Galen was born in 129 CE and came much later than Hippocrates. Galen respected many of Hippocrates’ teachings, mainly accepting the theory of the four humors. He based much of his reasoning about pathology on it. 17 out of the 22 volumes he collected are of “On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Human Body”

“Theory of demonstration”

Developed by Galen, the “theory of demonstration” involved making careful observations and applying logic to discover medical truths. He conducted experiments on live animals, including oxen, horses, sheep, and swine, as well as on monkeys. A notable experiment included one on live pigs, where he cut nerve bundles one at a time to demonstrate which functions were affected by each one. The Galen’s Nerve, named after him, was the laryngeal nerve that was cut and caused the pig to stop squealing. His main practices were actually on pigs, as they were quite anatomically similar to humans. This was a public demonstration, and known as a vivisection experiment. Galen continued his careful observations. One of them being that the arteries carry blood rather than air, by differentiating the arteries from veins.

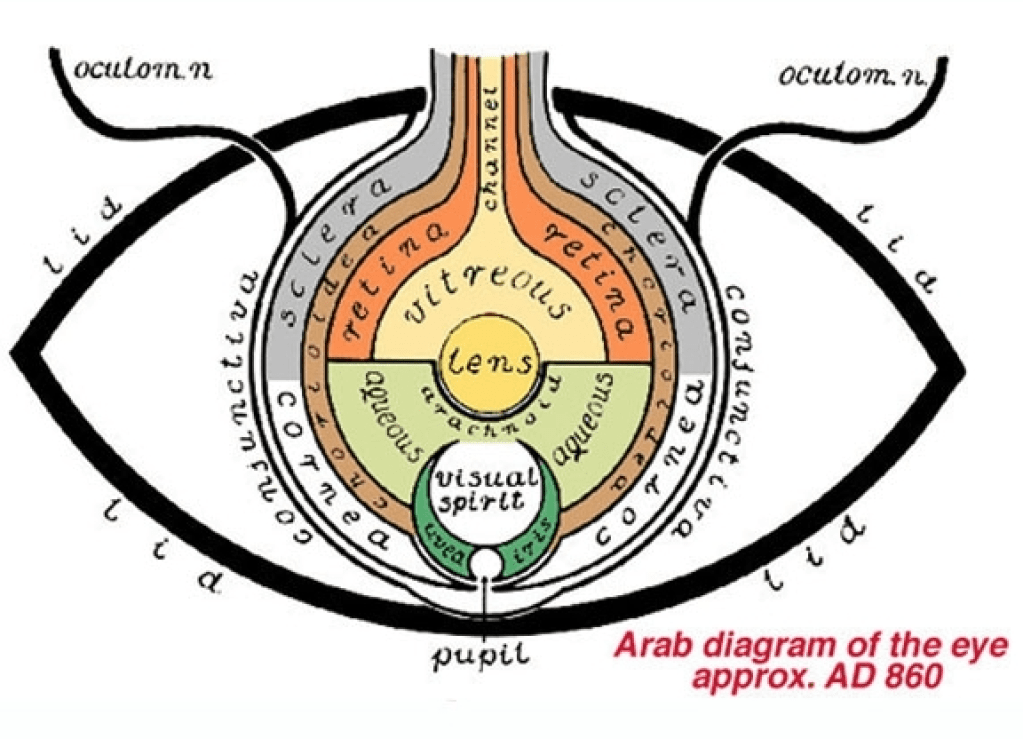

Onto another aspect of the body, Galen proposed that the primary structures of the eye consisted of distinct membranes and fluids. Structures included the cornea, the sclera, the lens capsule, the retina, and the structures surrounding the muscles of the eye.

However, not all of Galen’s studies were accurate. His studies on animal specimens led him to conclusions that certain animals were identical to humans. He also incorrectly believed that blood was formed in the liver, and that blood does not travel in a circulatory motion. These mistaken notions became established in the medical orthodoxy for many future centuries.

Leave a comment